Sugar beets were first introduced as an experiment in the late 1800s. When samples by local farmers J.W. Longstreth and H.C. Nichols were sent to the Kansas State Agricultural College in 1898 for analysis and showed with high percentages of sugar, the Lakin Investigator predicted the sugar beet industry would have a healthy future in Southwest Kansas. The Investigator wasn’t wrong.

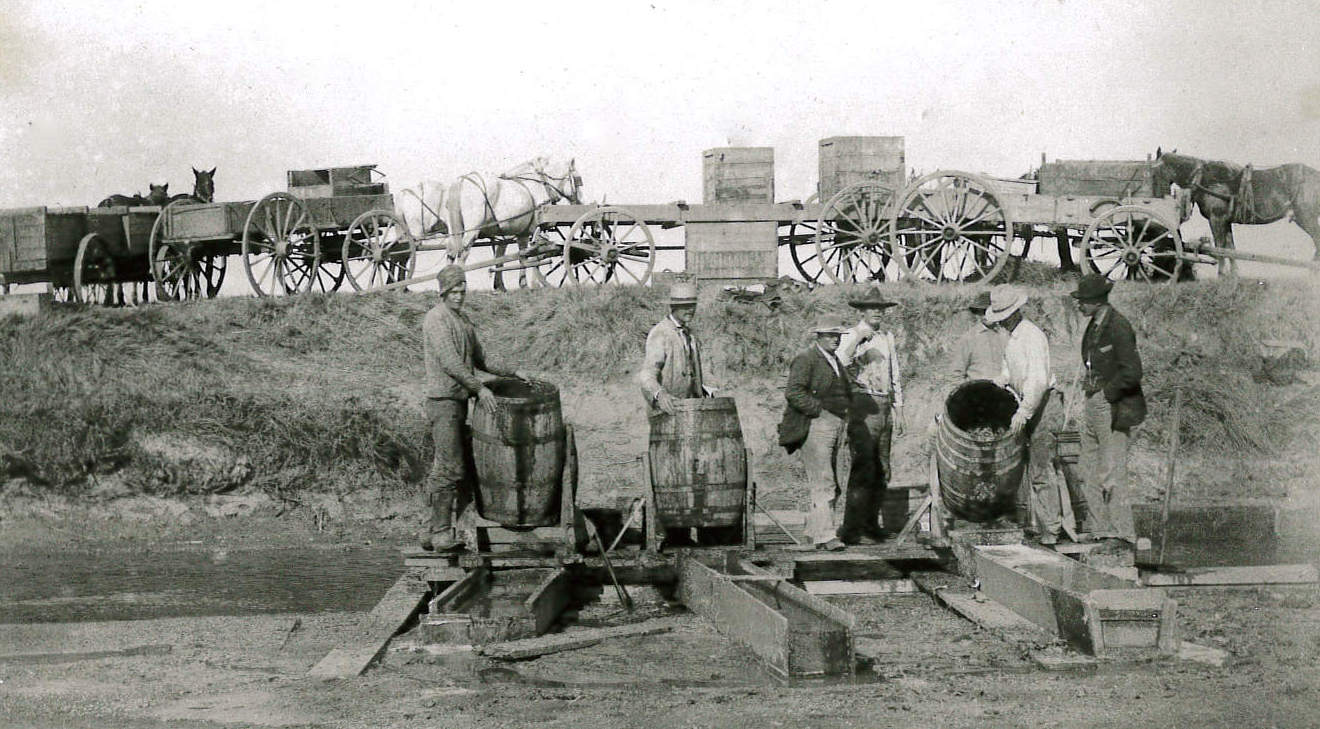

The state of Kansas put a bounty of $1 a ton on sugar beets in 1901. At that time, the crop was paying from $45 to $75 an acre, and the state’s bounty paid the freight to the refinery in Rocky Ford, Colorado. The Advocate reported that Finney, Hamilton and Kearny County had contracted for 700 acres of sugar beets, and the beets grown that year in the Deerfield neighborhood averaged a hearty nine tons to the acre. “For the first year’s work in this special crop, our farmers can congratulate themselves that they have fully demonstrated that they can grow this valuable, money making crop to advantage,” declared the Advocate.

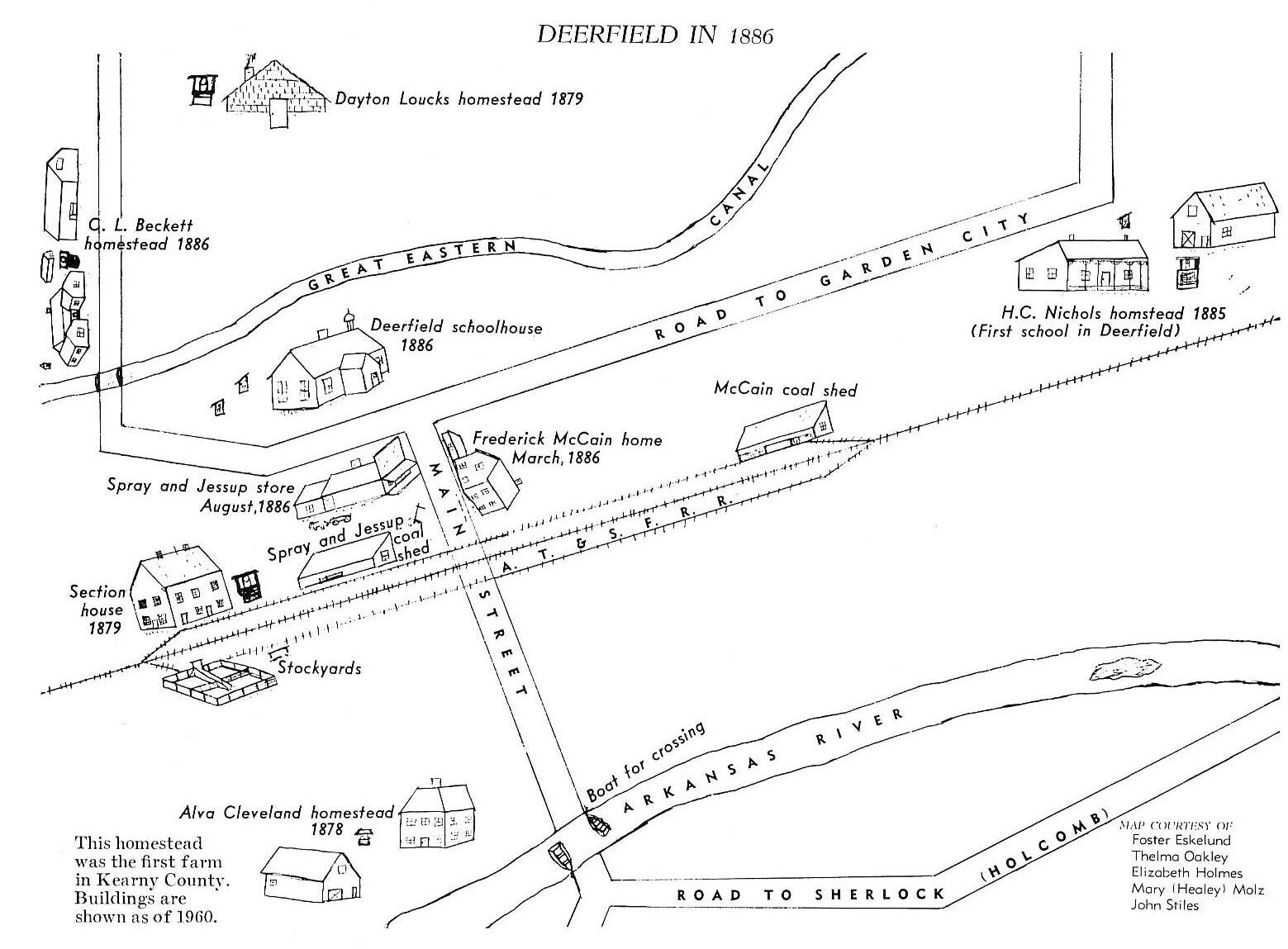

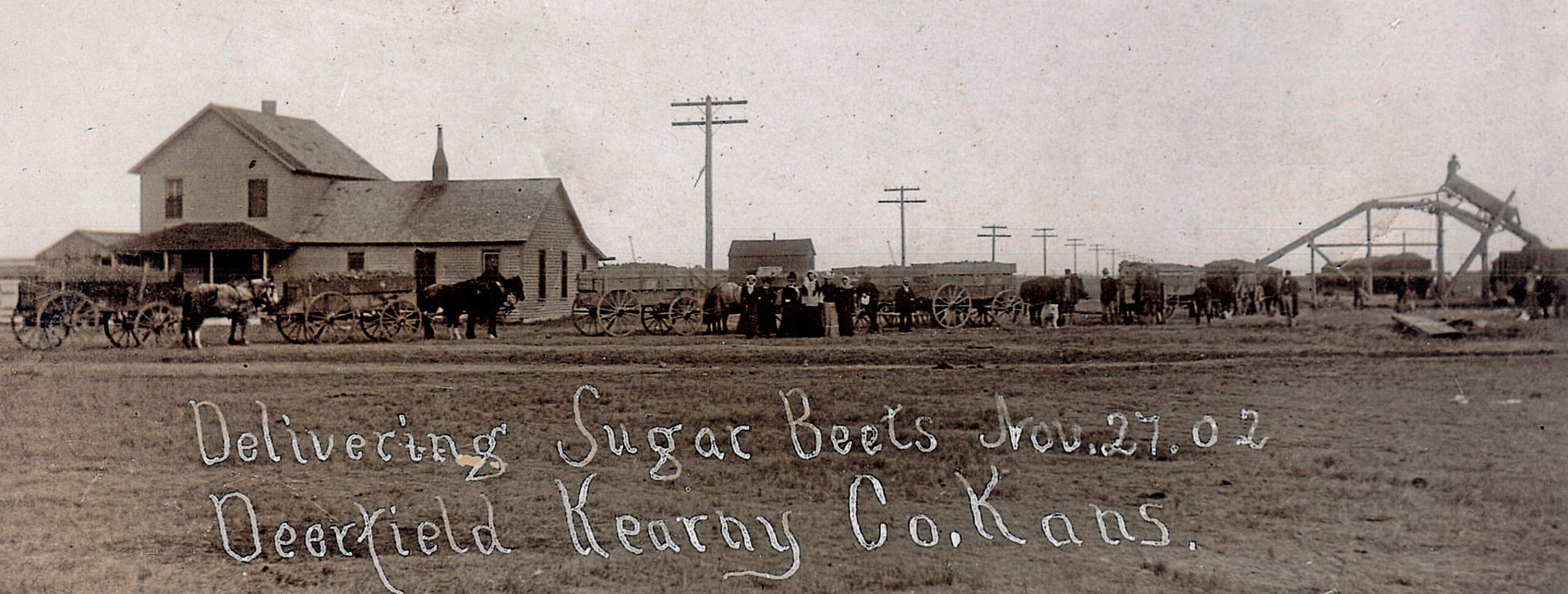

The American Sugar Beet Company of Rocky Ford contracted with area farmers for 500 acres of beets the following year, shipping the seed to Lakin’s depot in early spring 1902 at a cost of 10¢ per pound. The company also provided implements to plant and cultivate the crop which were paid for from the first beets harvested in November. Deerfield produced 2,155.5 tons or 1057 wagonloads, and Lakin farmers yielded a 1,295 ton-crop or 772 wagon loads. A total of 150 rail cars full of Kearny County beets were shipped to Rocky Ford. Climatic conditions, the rich Arkansas Valley soil, and established irrigation ditches made Kearny County a perfect spot for growing the crop, and talk had already begun about the need for a reservoir to store the ditch water until it was needed to irrigate the beet crops.

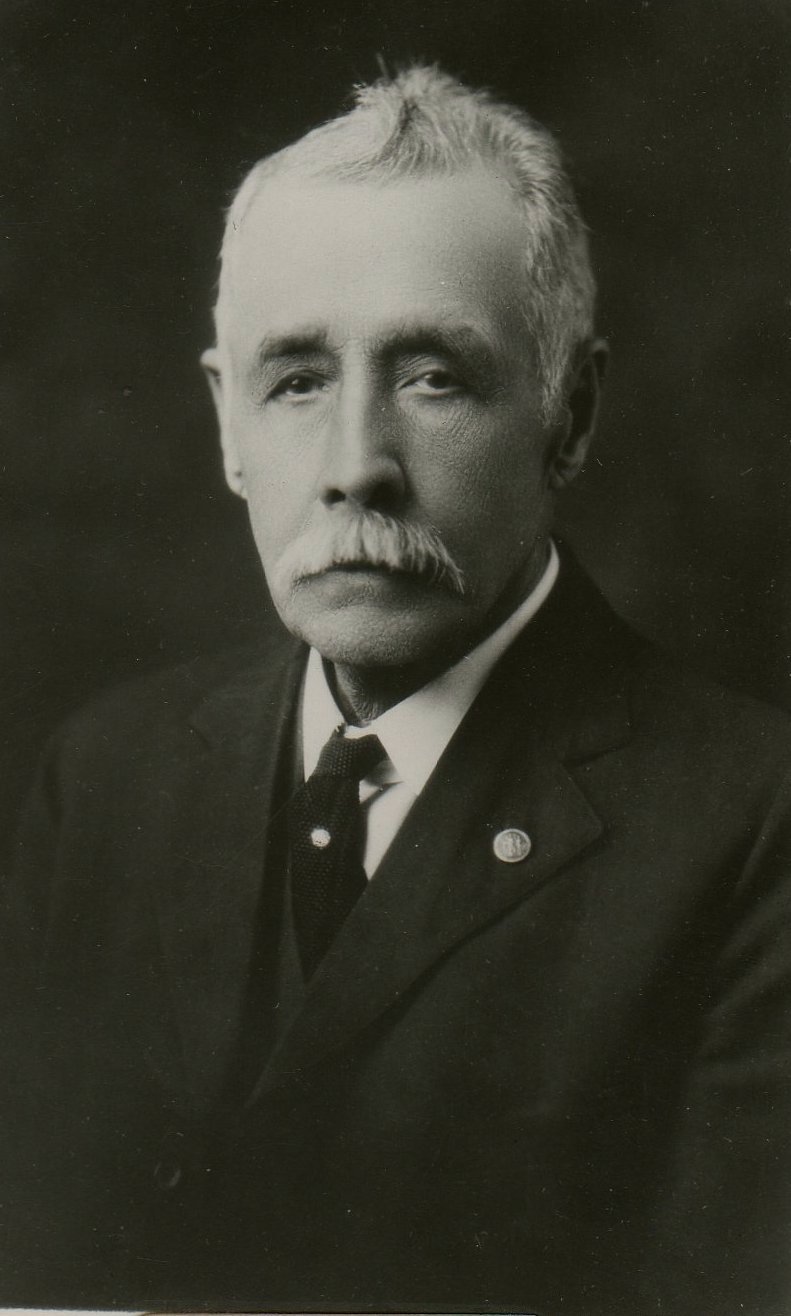

Local businessmen, farmers and citizens organized the Lakin Industrial Club in December of 1902 to further advance the development of the sugar beet industry “with a view of seeing a factory at this place.” Kearny County was the heart of the new industry for the next few years, but then a group of Colorado investors and Garden City businessmen organized the United States Sugar and Land Company in 1905, their sights set on developing the Garden City area. The hopes of a refinery being built in Kearny County were crushed when plans were announced to build in Garden City. Completed in November of 1906, 66,000 tons of beets were processed at the factory that first year.

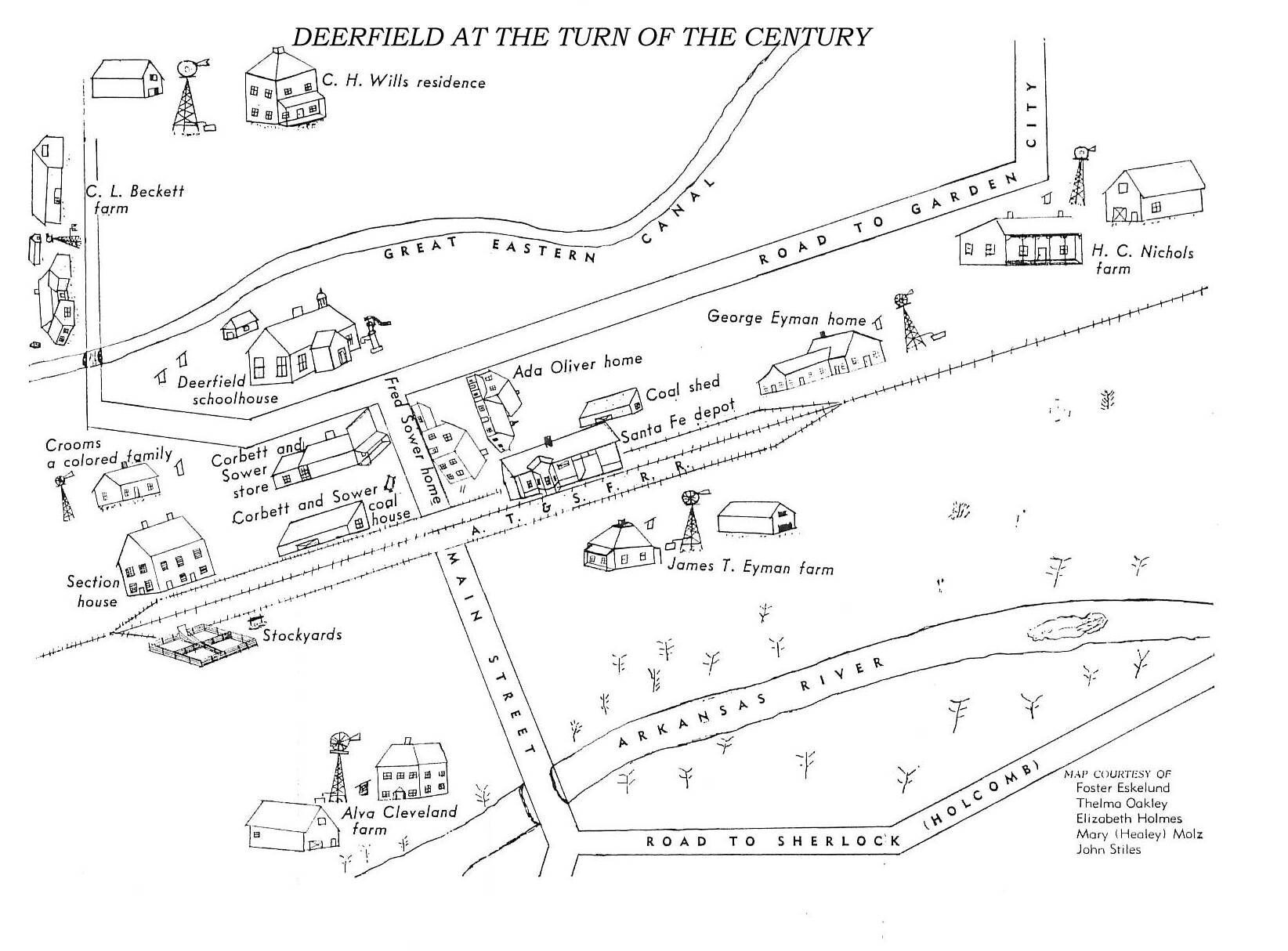

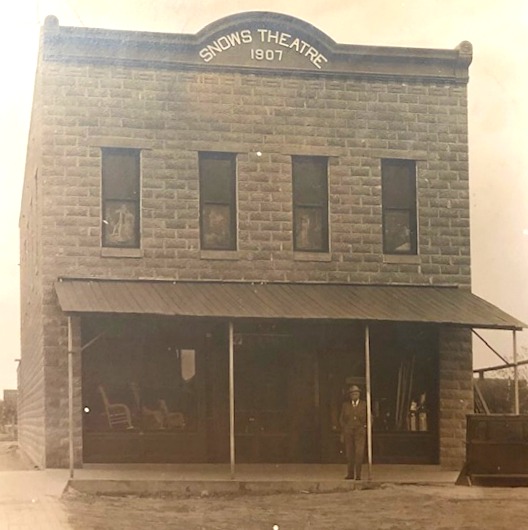

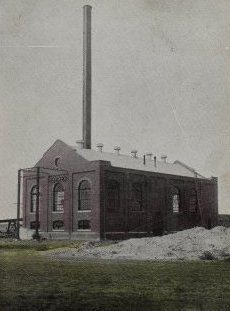

U.S. Sugar and Land also bought the Great Eastern Ditch and 12,000 acres of land which included the town of Deerfield and built several houses for their officials in the Deerfield area. For the next three to four years, Deerfield experienced great growth as more than 200 construction workers were employed for the company’s projects which included the construction of Lake McKinney and an electric plant to furnish power for the company’s irrigation wells to supplement the reservoir water. Under the U.S. Reclamation project, the government also built a power house near Deerfield which was eventually taken over by the sugar company along with a booster station and irrigation wells. In 1910, the Syracuse Journal reported that Deerfield “has a future before it that can hardly be beaten, the little town is steadily growing, and in time it will make one of the most progressive sites along the Santa Fe.”

In 1914, US Sugar and Land re-organized as Garden City Sugar And Land Company; then, in February 1920, the company became Garden City Company. That same year a block of 25,000 acres of company-owned land west of Garden City was turned over to tenant farmers. Hundreds of four-room houses were built on the land. In 1930, the company name was again changed and still remains today as The Garden City Company. By 1949, the corporation owned a stretch of land from Coolidge to Great Bend.

Obtaining a sufficient supply of beets for the factory became difficult after World War II so beets were introduced in the Ulysses and Scott City areas. This kept the factory going, but the extra freight to ship beets to the factory caused a heavy burden. Factory machinery had also become outdated. To keep profitable, the factory needed to be enlarged and modernized, but that was seen as an expensive and risky investment. The factory was shut down after the 1955 beet campaign and sold to the Holly Sugar Company which had no intention of ever operating the Garden City plant.

By 1972, only one Arkansas Valley sugar beet processing plant remained in operation, the American Crystal Sugar Company of Denver’s plant at Rocky Ford. The Garden City Company continued to raise sugar beets until 1974, shipping them to Rocky Ford by rail. That year, the mill closed its doors but a cooperative of sugar beet producers known as Colo-Kan Sugar Co. leased the mill from American Crystal Sugar. Decreased acreage and low prices for beets made the crop uneconomical to produce, and after four successive years of loss, Colo-Kan Sugar Co. terminated its lease following the 1978 harvest. The mill was permanently closed, effectively bringing an end to the once thriving sugar beet industry in Southwest Kansas.

SOURCES: A Brief History of “The Garden City Company” & “Sugar Factory” by W. F. Stoeckly; “The Sugar Beet Industry in Kansas” by Tiburgio J. Berber; History of Kearny County Vols. I & II; archives of Rocky Ford Tribune, The Syracuse Journal, Garden City Herald, The Evening Telegram, Garden City Telegram, Hutchinson News, Iola Register, Lakin Investigator, Advocate and Lakin Independent; and Museum archives.